We are awakened in the wee hours to the sound of bells chiming like nautical reindeer past the gatehouse, down the ramp and up our transom. DrC launches himself abruptly skyward. I put out a hand to stop him, "No. Don't worry. No kill."

"What?"

"No announcement, no kill."

This makes sense to my husband who, apparently not actually awake, simply flops back into somnolence and resumes snoring. It occurs to me to wonder how many patients were the beneficiary of this half-asleep wakefulness during his medical residency. In the meantime, Dulcinea rummages around the salon for a few minutes while she waits out the latest summer squall.

Dulcinea doesn't like summer in Auckland. Like the rest of us, she is waiting for weather that could be more reasonably credited with the sobriquet summer. Chill overcast mornings, frequent squalls, long days with no sun whatsoever, this is hardly summer. Dulcinea doesn't like prowling in the rain. Rain is wet. Wet is bad. Bad is not good. Not good means we must all suffer her frustration and unhappiness. There is scratching of the scratch post and nibbling at the nibble bowl and slurping at the slurp bowl. There is thumping up on to salon seats, bunks, cockpit benches and the boom. There is thumping down off seats, boom, and benches. All this activity is accompanied by the cheery sounds of Dulcinea's collar bell, only the most recent in my husband's efforts to prevent our cat from decimating New Zealand's precious wildlife. Then the squall stops, Dulcinea ventures out, peace and quiet descends, and I drop back into sleep.

Some unknown time later, bells chime and DrC repeats his leap out of bed act. This time I let him. Dulcinea is yelling about how wonderful she is, announcing to all and sundry that she is the most magnificent hunter on all the dock. I can also hear a buzzing whirr of wings. Experience compels me to tell my husband, "Beetle." In other words, don't bother getting out of bed. By the time you get up there, she will have eaten it. First, however, we must acknowledge the kill. I call out to my cat, "Good kitty. Wonderful kitty. Shut up you lovely wonderful hunter. Just eat it and shut up." This is all said in the most loving tones. It reminds me of those times when the girls were small and suckling at my breast when I would say in the most sweet, motherly tones, "Of course mommy loves you, you little shit. I can't believe you woke me up at 2am. Now just suck it up and go back to sleep, beautiful girl." A loud crunching sound from the salon affirms my conviction that it is merely the tone of voice that matters in situations like this one. Beetle wing sounds disappear, yowling stops. Quiet again.

The days when Dulcinea brought us wingless, legless crickets and laid them on our chest are long gone. I believe the night I launched her out the cabin, down the hall and halfway to La Paz was probably the end of that routine. Now she brings her catch only as far as the salon where she waits until she receives proper respect and accolades for her skill and cleverness. As soon as she catches something, she exults in her superior hunterlyness, shouting to the world about the wonder that is Dulcinea. As a rule, the yowling starts somewhere in the parking lot, then she'll trot past the gatehouse and down the ramp, across the dock and up into our boat chattering about the event all the way. The incongruity of her chirruping, shrieking merrowwing combined with the friendly tinkle of bells wakes me every time.

She is a very loud cat. She is probably the loudest cat in all of New Zealand. She is also an extremely good hunter. While we crossed the Pacific, Dulcinea focused her attentions on the squid and flying fish who inadvertently launched themselves into our orbit and from there succumbed to Dulci's voracious appetites. Here in Bayswater, she gives every domestic housecat a bad name as she brings home mice, birds, bugs, and on one memorable occasion a foot long rat. Worried that perhaps we might somehow be single-paw-ed-ly destroying a New Zealand endangered species, I verified with the harbor staff that there are no kiwis in Bayswater. In fact, there is nothing particularly precious in our neighborhood. The staff is all for Dulci eating the mice and rats, don't mind so much the occasional finch, and are rather hoping she'll take a liking to the flying roaches.

It's not as easy being the proud parent of such a voracious hunter, however. If Dulcinea were silent… if she could just eat with her feline mouth closed… it wouldn't be so bad. The nightly ritual, however, in which either DrC or I must go up, examine her kill, pet her, and then stumble back to our beds has grown stale. A few nights ago, her catch was a small bug of indeterminate species. She had it eaten before I had even turned around and started back down the companionway, upon which she started yowling again. I spin on one heel presented with the sight of that damn cat sitting next to her bowl quite clearly demanding that I feed her. "It's three o'clock in the morning and you couldn't be bothered to catch more than a half inch beetle and you want me to feed you?"

Apparently so.

Did I mention that she is loud?

Tonight, we are awakened by a third hunting alarm. Patting my husband on the shoulder, I go up, fill the dish, toss a cricket overboard, pat the cat, rub my tummy, and go back to bed. As I climb in, my husband mutters at me asking what I think I am about. "Why do you keep going up there?"

I groan as I settle back into the sheets, "I am completely pussy whipped."

Showing posts with label wildlife. Show all posts

Showing posts with label wildlife. Show all posts

Friday, March 02, 2012

Wednesday, January 05, 2011

Follow the Trail

I look around the disaster zone which is my daughters' dorm room and ask my husband, “They're joking, right?”

He shakes his head: sad, frustrated, mad. “I don't think so.”

It's Sunday. Sunday at Chicken House is a Day of Work. We take this weekly opportunity to clean the house from end to end, load up the pantry with groceries, engage in serious, hard-core exercise, and study study study. I don't know that we ever consciously set out to position ourselves 180 degrees from our Christian neighbors and friends, but it's not an unhappy coincidence. There is an agreement that in addition to the toilet, shower, kitchen floor, and laundry, everyone is also required to straighten up their personal space with an eye towards removing every possible temptation to the local ant population. So DrC and I are standing, fists clenched tightly and propped aggressively on hips, to survey the results of their effort to achieve a Minimum Standard of Cleanliness.

DrC and I are not unreasonable in our fanatic insistence on cleanliness. Our concern is not founded in anything as silly as a fear of germs and bacteria; We actually welcome challenges to our immune system in the form of random strangers, poor personal hygiene, and water from suspect sources. The problem is Chicken House.

Chicken House is constructed on top of an enormous infestation of alien attack ants. These mutant black creatures have the ability to detect microscopic bits of pain au chocolate and honey drips, establishing a one inch wide trail stretching from the back door, down the hall to the living room, up on to the coffee table, over a casually draped jumper, and directly to a chunk of scone lodged in the starboard couch cushion. I sit down in the morning to finish my latte and grind my inbox down to zero. When I glance up a few minutes later, the kitchen counters are literally awash in a roiling mass of small dark invaders. They know our house schedule, architectural inadequacies, and eating habits with Google-level privacy invasion precision. If we wait patiently enough, I know eventually we'll catch the Ant Street View vehicles roaming the house snapping 360 pictures of everything we own. I'm hoping I'm not naked at the time.

Do not under any circumstances protest that ants are not sentient. If you can say that with a straight face, you've never lived with ants. Ants know all, see all. They are more clever and more ubiquitous than any omniscient deity. Like human babies, they can defy physical law and pass through openings that are considerably smaller than themselves. Ants are adaptive – block their entrance with poison gas or paprika, chewing gum or bait traps, and your average ant community will reroute faster than Internet backbone servers.

Ants are also stubborn, even more stubborn than teenagers. Our ants – and I say “our” with no small degree of irony – refuse to give up their basic contention that Chicken House and all its contents belong to the Ants. Like college roommates, what is mine is mine and what is yours is mine. It's not enough that we carefully compile all our vegie scraps into a bucket and pile it in the backyard for composting providing an endless source of food. No, it's also necessary to drink our last beer, eat the last batch of microwave popcorn, and borrow our last clean towel.... ant-iphorically speaking.

All winter long we've waged urban warfare against the ants, attempting to create safe zones within Chicken House. While conceding to the complete lawlessness of the kitchen wherein we just hope to eat our meal fast enough that it doesn't get carried away, we have been able to fight the ants back in the parental bedroom, my office, and the rooms which serve the bath, toilet, and shower. The living room and kid dorm, however, are a standing source of extreme familial strife. On the one side are parental edicts: no eating, no dishes, no candy, no cookies, nothing edible period no exceptions ever. On the other side is childhood rebellion.

So the ants are winning.

He shakes his head: sad, frustrated, mad. “I don't think so.”

It's Sunday. Sunday at Chicken House is a Day of Work. We take this weekly opportunity to clean the house from end to end, load up the pantry with groceries, engage in serious, hard-core exercise, and study study study. I don't know that we ever consciously set out to position ourselves 180 degrees from our Christian neighbors and friends, but it's not an unhappy coincidence. There is an agreement that in addition to the toilet, shower, kitchen floor, and laundry, everyone is also required to straighten up their personal space with an eye towards removing every possible temptation to the local ant population. So DrC and I are standing, fists clenched tightly and propped aggressively on hips, to survey the results of their effort to achieve a Minimum Standard of Cleanliness.

DrC and I are not unreasonable in our fanatic insistence on cleanliness. Our concern is not founded in anything as silly as a fear of germs and bacteria; We actually welcome challenges to our immune system in the form of random strangers, poor personal hygiene, and water from suspect sources. The problem is Chicken House.

Chicken House is constructed on top of an enormous infestation of alien attack ants. These mutant black creatures have the ability to detect microscopic bits of pain au chocolate and honey drips, establishing a one inch wide trail stretching from the back door, down the hall to the living room, up on to the coffee table, over a casually draped jumper, and directly to a chunk of scone lodged in the starboard couch cushion. I sit down in the morning to finish my latte and grind my inbox down to zero. When I glance up a few minutes later, the kitchen counters are literally awash in a roiling mass of small dark invaders. They know our house schedule, architectural inadequacies, and eating habits with Google-level privacy invasion precision. If we wait patiently enough, I know eventually we'll catch the Ant Street View vehicles roaming the house snapping 360 pictures of everything we own. I'm hoping I'm not naked at the time.

Do not under any circumstances protest that ants are not sentient. If you can say that with a straight face, you've never lived with ants. Ants know all, see all. They are more clever and more ubiquitous than any omniscient deity. Like human babies, they can defy physical law and pass through openings that are considerably smaller than themselves. Ants are adaptive – block their entrance with poison gas or paprika, chewing gum or bait traps, and your average ant community will reroute faster than Internet backbone servers.

Ants are also stubborn, even more stubborn than teenagers. Our ants – and I say “our” with no small degree of irony – refuse to give up their basic contention that Chicken House and all its contents belong to the Ants. Like college roommates, what is mine is mine and what is yours is mine. It's not enough that we carefully compile all our vegie scraps into a bucket and pile it in the backyard for composting providing an endless source of food. No, it's also necessary to drink our last beer, eat the last batch of microwave popcorn, and borrow our last clean towel.... ant-iphorically speaking.

All winter long we've waged urban warfare against the ants, attempting to create safe zones within Chicken House. While conceding to the complete lawlessness of the kitchen wherein we just hope to eat our meal fast enough that it doesn't get carried away, we have been able to fight the ants back in the parental bedroom, my office, and the rooms which serve the bath, toilet, and shower. The living room and kid dorm, however, are a standing source of extreme familial strife. On the one side are parental edicts: no eating, no dishes, no candy, no cookies, nothing edible period no exceptions ever. On the other side is childhood rebellion.

So the ants are winning.

Wednesday, November 03, 2010

Not Charlotte

It started months ago. A small spider took up residence in the corner of the kitchen window next to the stove. I don't know why we didn't remove it. DrC didn't, the girls would never think to do so, and I just shrugged and probably thought it was someone else's (e.g. the Man's) problem. Even small, she was very black and very spider-like.

I can pinpoint the date that I decided I liked her and wanted to keep her. It was the morning I was standing semi-comatose, warming my hands over the stove as the espresso brewed and noted that she had caught three ants in the night. Any ally in our ongoing war against the Chicken House Ants is welcome. I poured myself a latte, toasted the newest member of the family, and went to work.

This is not the first time the Conger clan has hosted a spider. We used to watch with fascination as spiders would build elaborate webs between the newell posts on the front porch of our West Seattle home. The dew would dust these complicated constructions and provide an endless source of fractal entertainment throughout the fall. The side yard played host on multiple occasions to the million scattered mobile flying dots of spider egg bursts. Every single spider invasion – whether in the lifelines in Canada or in the plants on the dining room table in Philadelphia – has been a source of pleasure, interest, and education for my husband, myself, and now our children.

Honestly, the only spider scare we've ever experienced was a truly notable and hysterically funny encounter between Jaime and a 13 cm spider in the Karangahake Gorge a few months go. I can't remember the last time the entire family laughed so hard as when Jaime came bursting out of that cave screaming and kareening down the trail at high speed with her hair on fire. Even she found the whole thing amusing after we finally caught up with her, calmed her down, reassured her that there were no signs of spiders anywhere on or near her and most particularly not in her hair. You could almost say that we're a pro-spider family.

So she – our latest spider neighbor – settled in for the winter. But this spider isn't exactly a neighbor, now is she? Living in the kitchen, she's more like a quiet roommate. A quiet, growing roommate. We've watched her shed her skin, like a lobster, several times now. Our little spider has grown to nearly an inch now. Yesterday, she caught a horse fly, the day before an enormous moth. Her web stretches over the entire corner of the window – about a square foot. Mera witnessed the fly capture. It blundered into the web in one corner. Mera was doing the dishes and paused to watch our girl dash over, sedate the fly before it ripped the web apart, wrap it up, and drag it into the center of her lair. Short of an Animal Planet video, I'm not certain how Mera could have been treated to a better visual experience of spider dining.

DrC and I are waiting, I believe, on reproduction. I don't know why, but we're working under the operating assumption that our room mate is a girl. We've been trying to figure out how she'd get preggers, actually. There are no signs of little boy spiders anywhere near by. And if she's a he, he's not getting out there to spread the spider “word” and father a dynasty. So this strategy of “settling into the corner of a window in a house in Pukekohe” might prove an evolutionary dead end. What we're hoping, though, is that before establishing residence in the highly target rich environment of the Chicken House kitchen, there was an encounter between our room mate and another spider which is going to result ultimately in a big spider egg sack.

It also possible that she is just going to keep growing until Jaime freaks out and insists that “Either that spider goes, or I do.” And while I can understand her recent spider-paranoia given her caving experience, I'm going miss her. It's been nice having Jaime around all these years.

I can pinpoint the date that I decided I liked her and wanted to keep her. It was the morning I was standing semi-comatose, warming my hands over the stove as the espresso brewed and noted that she had caught three ants in the night. Any ally in our ongoing war against the Chicken House Ants is welcome. I poured myself a latte, toasted the newest member of the family, and went to work.

This is not the first time the Conger clan has hosted a spider. We used to watch with fascination as spiders would build elaborate webs between the newell posts on the front porch of our West Seattle home. The dew would dust these complicated constructions and provide an endless source of fractal entertainment throughout the fall. The side yard played host on multiple occasions to the million scattered mobile flying dots of spider egg bursts. Every single spider invasion – whether in the lifelines in Canada or in the plants on the dining room table in Philadelphia – has been a source of pleasure, interest, and education for my husband, myself, and now our children.

Honestly, the only spider scare we've ever experienced was a truly notable and hysterically funny encounter between Jaime and a 13 cm spider in the Karangahake Gorge a few months go. I can't remember the last time the entire family laughed so hard as when Jaime came bursting out of that cave screaming and kareening down the trail at high speed with her hair on fire. Even she found the whole thing amusing after we finally caught up with her, calmed her down, reassured her that there were no signs of spiders anywhere on or near her and most particularly not in her hair. You could almost say that we're a pro-spider family.

So she – our latest spider neighbor – settled in for the winter. But this spider isn't exactly a neighbor, now is she? Living in the kitchen, she's more like a quiet roommate. A quiet, growing roommate. We've watched her shed her skin, like a lobster, several times now. Our little spider has grown to nearly an inch now. Yesterday, she caught a horse fly, the day before an enormous moth. Her web stretches over the entire corner of the window – about a square foot. Mera witnessed the fly capture. It blundered into the web in one corner. Mera was doing the dishes and paused to watch our girl dash over, sedate the fly before it ripped the web apart, wrap it up, and drag it into the center of her lair. Short of an Animal Planet video, I'm not certain how Mera could have been treated to a better visual experience of spider dining.

DrC and I are waiting, I believe, on reproduction. I don't know why, but we're working under the operating assumption that our room mate is a girl. We've been trying to figure out how she'd get preggers, actually. There are no signs of little boy spiders anywhere near by. And if she's a he, he's not getting out there to spread the spider “word” and father a dynasty. So this strategy of “settling into the corner of a window in a house in Pukekohe” might prove an evolutionary dead end. What we're hoping, though, is that before establishing residence in the highly target rich environment of the Chicken House kitchen, there was an encounter between our room mate and another spider which is going to result ultimately in a big spider egg sack.

It also possible that she is just going to keep growing until Jaime freaks out and insists that “Either that spider goes, or I do.” And while I can understand her recent spider-paranoia given her caving experience, I'm going miss her. It's been nice having Jaime around all these years.

Thursday, December 10, 2009

Eaten Alive!

Isla San Francisco is a jewel in the chain of islands that line the Baja California Sur coastline from La Paz to Bahia de Los Angeles. A little bit of an island just east of San Evaristo, the island boasts three lovely anchorages, each offering protection from a different wind point. The views range from the wide open vista of the Sea of Cortez on the east side to an absolutely stunning panorama of the layered, sculpted Sierra de Gigantes. We always plan our trips through this region to include at least one - preferably several - days at Isla San Francisco where we hike, snorkel, and enjoy amazing sunrises and sunsets.

So it was with anticipation that we pulled into the southwest anchorage of Isla San Francisco. We had pulled anchor early in Los Gatos and motor sailed the 20 miles south in light, frustrating winds. The winds were so light at one point that we put the kids on harnesses and lines and threw them off the back to float along with us for a few miles as we transited the San Jose Channel. With dusk falling, we had a pleasant evening of rum drinks, rosemary beans, and fresh yeast rolls to look forward to as we tucked into the litter box, a shallow section of the anchorage on the very southern most tip just inside a natural breakwater.

The first few minutes went about as expected. A little kerfuffle skuffling over who does what as we settled in for the night. It’s Jaime’s night for dishes. No it’s not! It’s Mera’s. No it isn’t! I don’t CARE whose night it is, just get the dirty dishes off the d* table... You know. The usual.

Then they arrived. It was like a scene out of an Alfred Hitchcock movie. A cloud of insects perked up, noticed six juicy tasty creatures had pulled up a mere dozen yards off the shoreline, and swooped down upon us. The bug tornado consisted of a few bobos, a fleet of mosquitos, and about seven berjillion no-see-ums.

Slap. “Ouch! Ooow... Ow! Bugs!”

The crew scrambled out, “Get the screens!” “Where are they?” “Behind the freezer in the office... hurry!” “Close Jaime’s porthole, she pitched the screen overboard last week!” “Got the shower hatch!” “Screens up!”

The mosquitos buzzed in impotent fury at the screens. They lined up, an army of proboscis-wielding blood suckers waiting for us to get stupid and slip out the door for a moment of fresh air. But we were smarter than that! We were ready! We had Screens! So we settled down to eat, smugly assured of our safety.

Slap. Smack! “Ouch! Oooow.... Ow! Omigod what is that thing?”

The crew tumbled out of the salon seats, smacking our exposed arms and legs with a collective cry of “What the hell?” The air of the salon was alive with microscopic, fast moving, flying vampires each armed with a ray of sting-death. They would alight on an arm or leg and dig in for the duration, plumping up and leaving behind a small red dot which itched worse than a 10-day-old road rash scab.

There was nothing else we could do. We shut every window, dogged down all the hatches. This served to trap a metric buttload of no-see-ums inside the boat, but no new ones could sneak in. Then the entire family began to slap, smack, and smear. Smearing was for the nasty bastards who had already eaten. They would settle on the white ceiling, fat black spots full of juicy gooey blood, slow and lethargic as they indulged in a post-feast siesta. These evil minions of bloody doom were the easy ones to kill with a well placed thumb. We spent the night huddled under sheets with the windows shut and the fans on, dying from a combination of slow blood loss and incredible, suffocating heat.

At the first glimmer of dawn, we ran away. We pointed the boat into the wind, fired up both engines, and tried to blow the remaining bugs out of the boat. It didn’t work. The entire day was spent eliminating black terror dots. The most effective method was to go to a no-see-um hideout... say the cockpit... and bare two fat juicy calves then wait. Wait for it. Wait for it. Slap! Another one down. We eliminated thousands using this method until our calves and forearms were a solid smear of jejenay guts. The only creatures with a stronger blood lust than no-see-ums are apparently my husband and children when exacting revenge.

Even so, the battle was a draw leaving everyone on the boat looking very much as though we had caught a particularly virulent strain of the measles. We were exhausted from lack of sleep, tension, and itchiness. Dean slapped cortisone on everyone, poured two rums down each of the adults, and sent everyone to bed early. We’re told it will only take a week or so for the red spots and itchiness to fade. I suspect it will take longer for my high-strung family to relax enough to not smack every black dot they see.

So it was with anticipation that we pulled into the southwest anchorage of Isla San Francisco. We had pulled anchor early in Los Gatos and motor sailed the 20 miles south in light, frustrating winds. The winds were so light at one point that we put the kids on harnesses and lines and threw them off the back to float along with us for a few miles as we transited the San Jose Channel. With dusk falling, we had a pleasant evening of rum drinks, rosemary beans, and fresh yeast rolls to look forward to as we tucked into the litter box, a shallow section of the anchorage on the very southern most tip just inside a natural breakwater.

The first few minutes went about as expected. A little kerfuffle skuffling over who does what as we settled in for the night. It’s Jaime’s night for dishes. No it’s not! It’s Mera’s. No it isn’t! I don’t CARE whose night it is, just get the dirty dishes off the d* table... You know. The usual.

Then they arrived. It was like a scene out of an Alfred Hitchcock movie. A cloud of insects perked up, noticed six juicy tasty creatures had pulled up a mere dozen yards off the shoreline, and swooped down upon us. The bug tornado consisted of a few bobos, a fleet of mosquitos, and about seven berjillion no-see-ums.

Slap. “Ouch! Ooow... Ow! Bugs!”

The crew scrambled out, “Get the screens!” “Where are they?” “Behind the freezer in the office... hurry!” “Close Jaime’s porthole, she pitched the screen overboard last week!” “Got the shower hatch!” “Screens up!”

The mosquitos buzzed in impotent fury at the screens. They lined up, an army of proboscis-wielding blood suckers waiting for us to get stupid and slip out the door for a moment of fresh air. But we were smarter than that! We were ready! We had Screens! So we settled down to eat, smugly assured of our safety.

Slap. Smack! “Ouch! Oooow.... Ow! Omigod what is that thing?”

The crew tumbled out of the salon seats, smacking our exposed arms and legs with a collective cry of “What the hell?” The air of the salon was alive with microscopic, fast moving, flying vampires each armed with a ray of sting-death. They would alight on an arm or leg and dig in for the duration, plumping up and leaving behind a small red dot which itched worse than a 10-day-old road rash scab.

There was nothing else we could do. We shut every window, dogged down all the hatches. This served to trap a metric buttload of no-see-ums inside the boat, but no new ones could sneak in. Then the entire family began to slap, smack, and smear. Smearing was for the nasty bastards who had already eaten. They would settle on the white ceiling, fat black spots full of juicy gooey blood, slow and lethargic as they indulged in a post-feast siesta. These evil minions of bloody doom were the easy ones to kill with a well placed thumb. We spent the night huddled under sheets with the windows shut and the fans on, dying from a combination of slow blood loss and incredible, suffocating heat.

At the first glimmer of dawn, we ran away. We pointed the boat into the wind, fired up both engines, and tried to blow the remaining bugs out of the boat. It didn’t work. The entire day was spent eliminating black terror dots. The most effective method was to go to a no-see-um hideout... say the cockpit... and bare two fat juicy calves then wait. Wait for it. Wait for it. Slap! Another one down. We eliminated thousands using this method until our calves and forearms were a solid smear of jejenay guts. The only creatures with a stronger blood lust than no-see-ums are apparently my husband and children when exacting revenge.

Even so, the battle was a draw leaving everyone on the boat looking very much as though we had caught a particularly virulent strain of the measles. We were exhausted from lack of sleep, tension, and itchiness. Dean slapped cortisone on everyone, poured two rums down each of the adults, and sent everyone to bed early. We’re told it will only take a week or so for the red spots and itchiness to fade. I suspect it will take longer for my high-strung family to relax enough to not smack every black dot they see.

Wednesday, December 02, 2009

A Little Extra Protein

A high pitched scream fills the boat, emanating from the salon. I leap out of the starboard bow where I am looking for a replacement bulb for the deck light and grab the advanced medical kit en route. A scream like that must mean a major knife cut. “What is it!? Who is it?!”

A gasp of horror and a huge indrawn breath from Jaime as I enter the salon, “OH MY GOD Mom, it MOVED.” She is standing at the table staring aghast at a bin of flour.

I draw a blank, “It moved.”

“The flour. It MOVED. Oh my god... LOOK it's moving again!!!” Mera and Aeron peer at the open container.

Aeron notes calmly, “She's right. It moves.” Why look at that. She pokes the powder with a testing finger and watches the entire mass roil slightly. “Cool.”

Mera doesn't think it's cool. Mera is a bit disgusted, “Eeew. What is wrong with it?”

“What is wrong with it? What is WRONG with it?! It's alive, that's what's WRONG with it!” Jaime shouts.

Okay, no blood, no band-aid. I put down the med kit and join the girls to stare at the teeming mass of bugs in our erstwhile dinner rolls. Apparently, we are not going to be having garlic bread with dinner this evening. I attempt to placate my eldest, “It's not really that bad. Just a bit of extra protein.”

She shoots me a classic teenage look of disgust and contempt. I'm worse than the flour. “No way. No -way- I am eating anything made with that.”

The gauntlet now thrown, I am tempted to get to work making yeast bread. However, when I pick up the container, a good dozen black moving creatures rise to the top and giggle at me. I swear I hear little chitters and snickers. I swallow both my pride and my gorge and admit, “Okay, you're probably right. There's not much we can do with this.”

Aeron looks disappointed, “Can I keep em?”

Jaime steps up, all officialdom, “No. You may not Keep M. Those are bugs. We do not want bugs on the boat.”

It's true. We don't want bugs on the boat. Bugs on the boat are a very Bad Thing. There are two basic kind of bugs you really do not want on a boat: weevils in the flour and roaches on the floor. Of the two, however, weevils are the easier problem to solve. “I have to agree with your sister, Aeron. We don't want weevils on the boat. You can throw them overboard.”

Mera asks, “Do they float?”

“More to the point, do they swim!?” Aeron is delighted with her new project. The flour bin gets swooped up, and my spawn are off to the transom where they throw flour and weevils around for 15 minutes testing such important scientific questions as: Do weevils fly? Why does flour float? Why do weevils sink? Why does flour clump in the salt water? What happens when you throw the flour upwind? and Just how much flour can we get on the boat before Mom's head explodes?

Glad someone is having fun. DrC says he saw a roach last night. All I can say is that he'd better be wrong, or we're going to need that medical kit after all. I'm going to have to kill myself.

A gasp of horror and a huge indrawn breath from Jaime as I enter the salon, “OH MY GOD Mom, it MOVED.” She is standing at the table staring aghast at a bin of flour.

I draw a blank, “It moved.”

“The flour. It MOVED. Oh my god... LOOK it's moving again!!!” Mera and Aeron peer at the open container.

Aeron notes calmly, “She's right. It moves.” Why look at that. She pokes the powder with a testing finger and watches the entire mass roil slightly. “Cool.”

Mera doesn't think it's cool. Mera is a bit disgusted, “Eeew. What is wrong with it?”

“What is wrong with it? What is WRONG with it?! It's alive, that's what's WRONG with it!” Jaime shouts.

Okay, no blood, no band-aid. I put down the med kit and join the girls to stare at the teeming mass of bugs in our erstwhile dinner rolls. Apparently, we are not going to be having garlic bread with dinner this evening. I attempt to placate my eldest, “It's not really that bad. Just a bit of extra protein.”

She shoots me a classic teenage look of disgust and contempt. I'm worse than the flour. “No way. No -way- I am eating anything made with that.”

The gauntlet now thrown, I am tempted to get to work making yeast bread. However, when I pick up the container, a good dozen black moving creatures rise to the top and giggle at me. I swear I hear little chitters and snickers. I swallow both my pride and my gorge and admit, “Okay, you're probably right. There's not much we can do with this.”

Aeron looks disappointed, “Can I keep em?”

Jaime steps up, all officialdom, “No. You may not Keep M. Those are bugs. We do not want bugs on the boat.”

It's true. We don't want bugs on the boat. Bugs on the boat are a very Bad Thing. There are two basic kind of bugs you really do not want on a boat: weevils in the flour and roaches on the floor. Of the two, however, weevils are the easier problem to solve. “I have to agree with your sister, Aeron. We don't want weevils on the boat. You can throw them overboard.”

Mera asks, “Do they float?”

“More to the point, do they swim!?” Aeron is delighted with her new project. The flour bin gets swooped up, and my spawn are off to the transom where they throw flour and weevils around for 15 minutes testing such important scientific questions as: Do weevils fly? Why does flour float? Why do weevils sink? Why does flour clump in the salt water? What happens when you throw the flour upwind? and Just how much flour can we get on the boat before Mom's head explodes?

Glad someone is having fun. DrC says he saw a roach last night. All I can say is that he'd better be wrong, or we're going to need that medical kit after all. I'm going to have to kill myself.

Saturday, August 29, 2009

Wildlife Viewing Area

“It's a deer,” my mother blurts out. She sounds excited. This encounter with wild life in a national park is a treat to be savored, a special part of the camping experience.

Aeron barely looks up to note calmly, “Mule deer.”

“What?” Mom glances over her shoulder. She stands posed at the edge of our camp site, straining to see better without taking the National Park Service forbidden step towards the ambling herbivore. She can barely contain herself, fingers itching to take a picture or touch the hide.

“Mule deer,” repeats my youngest, her head back in her coloring book. She explains without looking up again, “See the long ears and the markings on the coat?”

Mom checks the deer and sounds somewhat awed as she breathes, “Mule deer.” I'm not sure if it's the 8 year old naturalist or the two beautiful animals now striding slowly in our direction followed by a hyperventilating photographer from the Netherlands who clearly hasn't read the park rules.

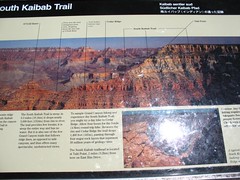

Probably both. Aeron and Mera are now officially sworn Junior Park Rangers in nine national parks: Petrified Forest, Bandalier, Aztec Ruins, Navajo National Monument, Grand Canyon, Bryce Canyon, Zion, Devil's Post Pile, and Yosemite. They can recite chapter and verse regarding park protection and maintenance procedure, distinguish between a sparrow and a white breasted nut hatch, report on the history and cultural significance of the ancestral Pueblan peoples, and talk intelligently about the geological formation of the Colorado River Plateau. The one-two punch of a year on a cruising sailboat followed by a month in our nation's best and perhaps most important cultural export has producd accomplished amateur naturalists with a respectful but rather casual view towards wild life. It's fair to say that if there is a polar opposite to nature deficit disorder, my girls are the poster children.

I'm proud of Mera and Aeron for all their work on their ranger patches. We started the program initially as an alternative to doing school on the road. However, the accrual of badges, patches, and parks soon took on a life of its own. They now actively seek out the Junior Ranger programs in each park and complete the activities without fuss or argument. My mother promised to make them Ranger vests on which they can sew all their awards and stick all their buttons. Both girls have expressed an interest in becoming rangers themselves when they grow up. They could surely do worse as a career.

I highly recommend to all parents that you look into the educational programs available through our nation's parks and forests. Even when you can't visit a park, there are usually many learning opportunities online. My only suggestion to the folks at the National Park Service is that they develop a comparable curriculum for the high school age groups. Jaime was, unfortunately, somewhat left out of the fun this summer. And unlike her mother, she's too old to just roll with it and do the “little kid work” to young to not lose her dignity in coloring animal pairs.

“And what's that?” Grandma Sue asks pointing at the black shape flitting through the dusk darkened boughs of Zion's campground.

“Bat, of course,” Aeron informs my mother. “They see by echo-location and eat mosquitoes so you have to like them.”

Okay, Junior Ranger Aeron. We have to like them.

Aeron barely looks up to note calmly, “Mule deer.”

“What?” Mom glances over her shoulder. She stands posed at the edge of our camp site, straining to see better without taking the National Park Service forbidden step towards the ambling herbivore. She can barely contain herself, fingers itching to take a picture or touch the hide.

“Mule deer,” repeats my youngest, her head back in her coloring book. She explains without looking up again, “See the long ears and the markings on the coat?”

Mom checks the deer and sounds somewhat awed as she breathes, “Mule deer.” I'm not sure if it's the 8 year old naturalist or the two beautiful animals now striding slowly in our direction followed by a hyperventilating photographer from the Netherlands who clearly hasn't read the park rules.

Probably both. Aeron and Mera are now officially sworn Junior Park Rangers in nine national parks: Petrified Forest, Bandalier, Aztec Ruins, Navajo National Monument, Grand Canyon, Bryce Canyon, Zion, Devil's Post Pile, and Yosemite. They can recite chapter and verse regarding park protection and maintenance procedure, distinguish between a sparrow and a white breasted nut hatch, report on the history and cultural significance of the ancestral Pueblan peoples, and talk intelligently about the geological formation of the Colorado River Plateau. The one-two punch of a year on a cruising sailboat followed by a month in our nation's best and perhaps most important cultural export has producd accomplished amateur naturalists with a respectful but rather casual view towards wild life. It's fair to say that if there is a polar opposite to nature deficit disorder, my girls are the poster children.

I'm proud of Mera and Aeron for all their work on their ranger patches. We started the program initially as an alternative to doing school on the road. However, the accrual of badges, patches, and parks soon took on a life of its own. They now actively seek out the Junior Ranger programs in each park and complete the activities without fuss or argument. My mother promised to make them Ranger vests on which they can sew all their awards and stick all their buttons. Both girls have expressed an interest in becoming rangers themselves when they grow up. They could surely do worse as a career.

I highly recommend to all parents that you look into the educational programs available through our nation's parks and forests. Even when you can't visit a park, there are usually many learning opportunities online. My only suggestion to the folks at the National Park Service is that they develop a comparable curriculum for the high school age groups. Jaime was, unfortunately, somewhat left out of the fun this summer. And unlike her mother, she's too old to just roll with it and do the “little kid work” to young to not lose her dignity in coloring animal pairs.

“And what's that?” Grandma Sue asks pointing at the black shape flitting through the dusk darkened boughs of Zion's campground.

“Bat, of course,” Aeron informs my mother. “They see by echo-location and eat mosquitoes so you have to like them.”

Okay, Junior Ranger Aeron. We have to like them.

Monday, July 13, 2009

Cat On a Hot Plastic Dock

I hear a piercing scream from the port hull. Mera sounds terrified, frantic. There are loud thuds and bangs, a howl, and more screaming. Within a flash, I'm up and have launched myself out of bed, up the companion way and across the salon.

“Mera! Mera!! What is it? Are you okay? What happened?” The torrent of motherly catch phrases pours out of my mouth even before my brain has fully wakened out of a sound sleep to the situation. “Are you hurt?”

Dulcinea gives a triumphant growl and a sickening crunch is heard from Mera's room. The cat streaks between my legs and out the cockpit, a blur of feline aggression. Mera sounds like she's hyperventilating, “Mom... mom...”

But I know what's happened now. I know with a dread certainty that my pleasant dreams of young men with coconut oil are gone for at least an hour while I straighten out this mess and calm the family down. “Another grasshopper?” I guess.

“Yes. She she... she put it on my stomach.”

I try to imagine this. You're sound asleep, pleasantly dreaming of something less pornographic than what's going on in the rather twisted mind of your parent in the opposite hull – something age appropriate, mind you, probably featuring Robert Pattinson and ice cream cones -- when a 3 inch grasshopper is victoriously placed on your chest. A live 3 inch grasshopper with no legs. And if that isn't enough, at the same time a happy, loving cat is meowing an announcement of her gift in your ear. The grasshopper flaps and flutters. The cat purrs and merrows. And suddenly the thing flits up off your chest to land, say... on your face.

I move into her cabin and soothe Mera, “It's okay, hun. It's okay.” Not the grasshopper. We both know the grasshopper is not okay. We both know that if we turn on the light we're going to see legs on the floor. We both know that Mera is not okay either. Her heart is racing and she's fast approaching a pathological, long term horror of crickets. What's okay is the scream. She had a perfect right to scream and wake up the whole family. Aeron and I are in complete accord with Mera. This was worth an ear-piercing, heart thudding, terror inducing howl.

As if to confirm my words, Aeron says, “S'all right Mera. She left two in my room, but they were on the floor,” tacit acknowledgement that there is a limit to our patience, with ourselves, with our cat. If the grasshoppers are on the floor, you don't get to wake everyone up any more. Stepping on a dismembered wing is so common an occurrence as to not rank sufficiently horrific for even so much as a whimper. But a chest deposit? Okay, fair enough. Scream to your heart's content, Mera.

I soothe Mera with a hug and the deft removal of grasshopper parts from her hair. “It's okay, baby. Go back to sleep.” We both glance out the hatch at the distinctive sound of Dulcinea thudding down the dock, collar chiming, voice calling, “perrrupppppp, chirp, perrumeoooowppp” as she returns to her hunting grounds. Absently, I rub Mera's back, “There can't be that many more out there...”

“Mera! Mera!! What is it? Are you okay? What happened?” The torrent of motherly catch phrases pours out of my mouth even before my brain has fully wakened out of a sound sleep to the situation. “Are you hurt?”

Dulcinea gives a triumphant growl and a sickening crunch is heard from Mera's room. The cat streaks between my legs and out the cockpit, a blur of feline aggression. Mera sounds like she's hyperventilating, “Mom... mom...”

But I know what's happened now. I know with a dread certainty that my pleasant dreams of young men with coconut oil are gone for at least an hour while I straighten out this mess and calm the family down. “Another grasshopper?” I guess.

“Yes. She she... she put it on my stomach.”

I try to imagine this. You're sound asleep, pleasantly dreaming of something less pornographic than what's going on in the rather twisted mind of your parent in the opposite hull – something age appropriate, mind you, probably featuring Robert Pattinson and ice cream cones -- when a 3 inch grasshopper is victoriously placed on your chest. A live 3 inch grasshopper with no legs. And if that isn't enough, at the same time a happy, loving cat is meowing an announcement of her gift in your ear. The grasshopper flaps and flutters. The cat purrs and merrows. And suddenly the thing flits up off your chest to land, say... on your face.

I move into her cabin and soothe Mera, “It's okay, hun. It's okay.” Not the grasshopper. We both know the grasshopper is not okay. We both know that if we turn on the light we're going to see legs on the floor. We both know that Mera is not okay either. Her heart is racing and she's fast approaching a pathological, long term horror of crickets. What's okay is the scream. She had a perfect right to scream and wake up the whole family. Aeron and I are in complete accord with Mera. This was worth an ear-piercing, heart thudding, terror inducing howl.

As if to confirm my words, Aeron says, “S'all right Mera. She left two in my room, but they were on the floor,” tacit acknowledgement that there is a limit to our patience, with ourselves, with our cat. If the grasshoppers are on the floor, you don't get to wake everyone up any more. Stepping on a dismembered wing is so common an occurrence as to not rank sufficiently horrific for even so much as a whimper. But a chest deposit? Okay, fair enough. Scream to your heart's content, Mera.

I soothe Mera with a hug and the deft removal of grasshopper parts from her hair. “It's okay, baby. Go back to sleep.” We both glance out the hatch at the distinctive sound of Dulcinea thudding down the dock, collar chiming, voice calling, “perrrupppppp, chirp, perrumeoooowppp” as she returns to her hunting grounds. Absently, I rub Mera's back, “There can't be that many more out there...”

Wednesday, July 01, 2009

Alone Again

[Editor's Note: Written as we returned from Bahia de Los Angeles to Santa Rosalia in mid June.]

Something about timing precludes the Conger Clan from exploring new territory at the same time as every other boat in the cruising fleet. We headed north for the Vancouver Island inside passage about two months before everyone else. When it came time to head south to Zihau, we got down there at least three weeks before the rest of the troops. Now heading into Bahia de Los Angeles area north of Santa Rosalia, we leave the summer Sea of Cortez fleet in our wake and head into the wilderness toot sool. At least we're consistent.

For three weeks, we haven't seen another living cruiser. We've seen living souls, though few enough even of those. A couple of pangas, some sport fishers, a pair of tourists escorted out of one of the resorts. We even saw a quartet of hikers on the way up Volcano Coronado. These exceptions to prove the solitary rule, however, just make things a bit more interesting while leaving the cruising grounds isolated and beautiful.

Unexpectedly, the Sea of Cortez has literally flattened the family with its harsh, desolate beauty. This area makes Espiratu Santos look positively lush. There are no trees; In fact, in some places you would be hard pressed to find even so much as a blade of grass. Humans can barely shoe-horn an existence in the few tiny pocket arroyos and lagoons. Animals find the lifestyle nearly as challenging.

We often sail at roughly 2 knots. That's hardly a sail, I realize, but with no swell or wave action, we can float quietly and peacefully while DrC plays his guitar and the girls and I study. We don't have any where in particular to go so we just waft along, moving, I suspect, almost entirely on the tide. It's amazing how far you can go at 2 knots if there are no waves to slap you around.

Our patience is frequently rewarded by encounters with the abundant sea life. While the landscape is almost alien with its rocky, volcanic geology, the Sea of Cortez itself is so full of life we can hardly move the boat without running into something. What we believe to be fin whales are everywhere we go. We can see and hear them blowing all around us as we passage from one small anchorage to another. On several occasions, the big guys have come near the boat. Once, we all ran to the bow to watch three lurch past. There is no question the creatures were considerably longer than our boat. The tail fins alone looked nearly 10 feet from tip to tip if not wider. Two passed along side us just under the surface while a third decided to go straight under the boat. We gasped, ooh'd, ah'd, and panicked as the huge fin slid slowly through the tramps at about 20 feet below us. OMIGODWTF. I love whales, but I really think that they are creatures better seen from a distance. It's hard to be calm when a creature half again the length of your house gets a bit curious.

We have also seen several pods of feeding dolphins as well as whatever you call a bunch of very pleased-with-themselves seals. We hear coyotes on shore so there must be something somewhere to eat. When we anchor in turquoise waters off white sand beaches, the bottom 25 feet below us is so clear we can practically snorkel by sitting on the transom with a rum punch and peering over the side. And while our fishing luck continues to run towards nothing more exciting than sculpin and trigger fish, we could dine almost nightly on lobster and clams were we so inclined. The official going rate in these remote anchorages for lobster is five medium sized creatures for a box of orange juice and a 2 liter bottle of Fresca. Deep fish like tuna is a bit pricier, requiring us to hand over several tomatoes, a half dozen eggs, and a package of tortillas. The barter economy is live and well.

Without the distraction of buddy boats, fellow cruisers, or the temptations of town, we've settled into a steady routine. Morning is school and boat chores while underway or at anchor. A hot lunch, then we go our separate ways. If at an anchor, the children often take the dinghy and head off on their own adventures. The basic wildness of our girls grows daily, the freedom and safety and stunning natural beauty of the landscape bringing out the same in the spirits of our children. We snorkel and we hike. We study, watch movies, and practice our instruments. We read and read and read and read.

The regret and sadness is palpable on the boat as we make our way southwards back towards Santa Rosalia. Soon Daddy will leave for several months. Soon Don Quixote will be tied unnaturally to a dock in a harbor for months on end. Too soon we will be surrounded again in people, food, the Internet, and all sorts of tempting ways to spend our money. DrC is at the helm, Aeron in his lap. A world music mix plays Caribbean sounds as a background to swoosh of the beam sea and 15 knots of wind while the sun slowly sets on our last relaxed sail of the season. I lean into my husband's back with tears in my eyes and whisper in his ear, “We're not done yet.”

Something about timing precludes the Conger Clan from exploring new territory at the same time as every other boat in the cruising fleet. We headed north for the Vancouver Island inside passage about two months before everyone else. When it came time to head south to Zihau, we got down there at least three weeks before the rest of the troops. Now heading into Bahia de Los Angeles area north of Santa Rosalia, we leave the summer Sea of Cortez fleet in our wake and head into the wilderness toot sool. At least we're consistent.

For three weeks, we haven't seen another living cruiser. We've seen living souls, though few enough even of those. A couple of pangas, some sport fishers, a pair of tourists escorted out of one of the resorts. We even saw a quartet of hikers on the way up Volcano Coronado. These exceptions to prove the solitary rule, however, just make things a bit more interesting while leaving the cruising grounds isolated and beautiful.

Unexpectedly, the Sea of Cortez has literally flattened the family with its harsh, desolate beauty. This area makes Espiratu Santos look positively lush. There are no trees; In fact, in some places you would be hard pressed to find even so much as a blade of grass. Humans can barely shoe-horn an existence in the few tiny pocket arroyos and lagoons. Animals find the lifestyle nearly as challenging.

We often sail at roughly 2 knots. That's hardly a sail, I realize, but with no swell or wave action, we can float quietly and peacefully while DrC plays his guitar and the girls and I study. We don't have any where in particular to go so we just waft along, moving, I suspect, almost entirely on the tide. It's amazing how far you can go at 2 knots if there are no waves to slap you around.

Our patience is frequently rewarded by encounters with the abundant sea life. While the landscape is almost alien with its rocky, volcanic geology, the Sea of Cortez itself is so full of life we can hardly move the boat without running into something. What we believe to be fin whales are everywhere we go. We can see and hear them blowing all around us as we passage from one small anchorage to another. On several occasions, the big guys have come near the boat. Once, we all ran to the bow to watch three lurch past. There is no question the creatures were considerably longer than our boat. The tail fins alone looked nearly 10 feet from tip to tip if not wider. Two passed along side us just under the surface while a third decided to go straight under the boat. We gasped, ooh'd, ah'd, and panicked as the huge fin slid slowly through the tramps at about 20 feet below us. OMIGODWTF. I love whales, but I really think that they are creatures better seen from a distance. It's hard to be calm when a creature half again the length of your house gets a bit curious.

We have also seen several pods of feeding dolphins as well as whatever you call a bunch of very pleased-with-themselves seals. We hear coyotes on shore so there must be something somewhere to eat. When we anchor in turquoise waters off white sand beaches, the bottom 25 feet below us is so clear we can practically snorkel by sitting on the transom with a rum punch and peering over the side. And while our fishing luck continues to run towards nothing more exciting than sculpin and trigger fish, we could dine almost nightly on lobster and clams were we so inclined. The official going rate in these remote anchorages for lobster is five medium sized creatures for a box of orange juice and a 2 liter bottle of Fresca. Deep fish like tuna is a bit pricier, requiring us to hand over several tomatoes, a half dozen eggs, and a package of tortillas. The barter economy is live and well.

Without the distraction of buddy boats, fellow cruisers, or the temptations of town, we've settled into a steady routine. Morning is school and boat chores while underway or at anchor. A hot lunch, then we go our separate ways. If at an anchor, the children often take the dinghy and head off on their own adventures. The basic wildness of our girls grows daily, the freedom and safety and stunning natural beauty of the landscape bringing out the same in the spirits of our children. We snorkel and we hike. We study, watch movies, and practice our instruments. We read and read and read and read.

The regret and sadness is palpable on the boat as we make our way southwards back towards Santa Rosalia. Soon Daddy will leave for several months. Soon Don Quixote will be tied unnaturally to a dock in a harbor for months on end. Too soon we will be surrounded again in people, food, the Internet, and all sorts of tempting ways to spend our money. DrC is at the helm, Aeron in his lap. A world music mix plays Caribbean sounds as a background to swoosh of the beam sea and 15 knots of wind while the sun slowly sets on our last relaxed sail of the season. I lean into my husband's back with tears in my eyes and whisper in his ear, “We're not done yet.”

Sunday, December 07, 2008

Coals to Newcastle

“Blow holes at eleven o’clock,” Grandpa George calls from the helm. DrC lifts his head from his book and looks around, the girls scramble up from their cabins. Humps and fins at eleven were only the start. Within minutes, the crew spotted signs of whale in every cardinal direction.

We were entering Monterey Bay. The weather had been lovely all day, though the wind chose not to pick up until mid-afternoon. With the spinnaker finally flying, we were enjoying a pleasant downwind sail into Monterey Harbor, looking forward to a layover day in that famous California coastal town.

The whales provided quite a show. Huge humped backs mounded through the waves. Large spumes of air signaled the direction to point eyes, binoculars and cameras, fins and flukes slapped the water to get our attention.

At one point, I shouted, “Forward!” It’s all I could say as a humpback leaped out of the water roughly ten yards off the port bow, landing with a thunderous splash that sent spume up onto the bows and on to the faces of my gaping children. “Grab a line!” DrC and George both shouted. We all dived for a hand-hold in case the whale decided to take on a catamaran. The enormous mammal chose instead to slide a few feet past the port beam, leaving a fuming wake of bubbles and gratefully astonished sailors. I said shakily, “That was an amazing experience... one I might not want to repeat.”

Our bow whale only punctuated a day full of Discovery Channel moments. Seagulls spent the day playing tag with Don Quixote as they dove on our bait, drafted in our wind wake, and hitched the occasional ride on the bow. Mera whiled away several hours sitting in a bow seat counting jelly fish. DrC caught a mackerel and, after much discussion and many pictures, the family decided it was insufficiently tasty eating and threw it back. We barked at sea otters rolling in kelp, George took pictures of cormorants, pelicans, and other sea birds, and the girls tried to catch sight of plankton through a microscope. As we came into the harbor, we were greeted with the sight of hundreds of sea lions basking, barking and honking on the breakwater.

At sunset, we settled down to a bobbing anchor with curry, rice and mangos. Grandpa George finished his lesson on Hinduism as DrC and I finished our last sips of wine before stirring the wasp nest that is our family preparing for bed each night. Grandpa asked the table, “So girls! What should we do tomorrow in Monterey?”

Three girls chimed harmoniously, “Let’s go to the aquarium!!” DrC smiled, I shrugged, and George laughed. “Okay! Let’s go see some sea life.”

We were entering Monterey Bay. The weather had been lovely all day, though the wind chose not to pick up until mid-afternoon. With the spinnaker finally flying, we were enjoying a pleasant downwind sail into Monterey Harbor, looking forward to a layover day in that famous California coastal town.

The whales provided quite a show. Huge humped backs mounded through the waves. Large spumes of air signaled the direction to point eyes, binoculars and cameras, fins and flukes slapped the water to get our attention.

At one point, I shouted, “Forward!” It’s all I could say as a humpback leaped out of the water roughly ten yards off the port bow, landing with a thunderous splash that sent spume up onto the bows and on to the faces of my gaping children. “Grab a line!” DrC and George both shouted. We all dived for a hand-hold in case the whale decided to take on a catamaran. The enormous mammal chose instead to slide a few feet past the port beam, leaving a fuming wake of bubbles and gratefully astonished sailors. I said shakily, “That was an amazing experience... one I might not want to repeat.”

Our bow whale only punctuated a day full of Discovery Channel moments. Seagulls spent the day playing tag with Don Quixote as they dove on our bait, drafted in our wind wake, and hitched the occasional ride on the bow. Mera whiled away several hours sitting in a bow seat counting jelly fish. DrC caught a mackerel and, after much discussion and many pictures, the family decided it was insufficiently tasty eating and threw it back. We barked at sea otters rolling in kelp, George took pictures of cormorants, pelicans, and other sea birds, and the girls tried to catch sight of plankton through a microscope. As we came into the harbor, we were greeted with the sight of hundreds of sea lions basking, barking and honking on the breakwater.

At sunset, we settled down to a bobbing anchor with curry, rice and mangos. Grandpa George finished his lesson on Hinduism as DrC and I finished our last sips of wine before stirring the wasp nest that is our family preparing for bed each night. Grandpa asked the table, “So girls! What should we do tomorrow in Monterey?”

Three girls chimed harmoniously, “Let’s go to the aquarium!!” DrC smiled, I shrugged, and George laughed. “Okay! Let’s go see some sea life.”

Thursday, August 28, 2008

Sail Gale Whale Ale Day

The trip was roughly 35 nautical miles if you followed the coast line from Winter Harbor, across to Cape Cook, around Brooks Peninsula, and over to the tuck into beautiful little Columbia Cove. Other than rounding Cape Scott, this trip around Brooks Peninsula is considered by many to be the hairiest part of any passage up or down the west coast of Vancouver Island.

Brooks is a thumb of land pushing into the Pacific like a hitch hiker grabbing the nearest earthly plate to drift northwards. Apparently, this nearly square jut of land is the only part of Vancouver not covered by glaciers during the last ice age. It stands several thousand feet tall and funnels the prevailing summer northeasterly in a vicious hook around Cape Cook and Solander Island where winds are routinely 30 to 40 and at least 10 to 15 higher than everywhere else.

As a result, we all timed the weather window carefully, hanging on hooks in or near Winter Harbor for a few days until satisfied with the reports off Solander and South Brooks. The sail boats were, of course, the first to leave the harbors. We swarmed out of Quatsino Sound, little pickup sticks bouncing vertically on the waves as we coalesced from north and west towards our course at the first waypoint off Kwakiutl Point. The wind freshened inexplicably from the east to 15 and the horizon sparkled with the handkerchief dots of main sails and jibs happily taking advantage of the beam reach for the first leg.

Just as all our sails went up, the power boaters steamed by thumping out cross wakes which were immediately lost in the developing chop created by an easterly wind and a northwesterly swell. Their objectives were no doubt considerably more ambitious than our own, bypassing the hidden coves of South Brooks entirely and heading deep into the friendly harbors and calm waters of Kyuquot Channel. There was also the practical consideration of the weather report. Winds nasty in the morning, dying off mid day, returning with a vengeance in late afternoon. Our p/v compatriots were simply getting while the getting was good.

We, however, were sailing into a fog bank as the winds shifted finally to their usual northwest and picked up to 20. The seas were only 2 meters. Only. The girls and I are complete noobs in the world of oceanic voyaging so six feet of steep wave with white caps was both intimidating and sickening. One by one, the girls went down with gimpy tummy. No one tossed anything smelly, but I settled them all down with blankies, stuffed animals, and motherly love, and they promptly followed the body’s most useful defense against seasickness -- they passed out. This left Dr C and I on the deck with no company. All the other boats, the shore, and the horizon were lost in a dense blanket of mist.

I said 35 miles, right? But that was, of course, assuming we followed the coast line. We never follow the coast line. We never follow a straight line. We are a sail boat, so of course the wind never permits us to travel the shortest distance. Instead, we headed off into the deep blue in a course somewhat orthogonal to our destination. The winds were cold and wet, the skies grey, the water slate and dusted with spray. Tracking via the chart plotter, backed up by our handheld GPS and chart, was the only indicator we were making progress. It all looked the same. Seas high and choppy, steep waves with short periods, wind steady 23 gusting occasionally to 30. Dr C kept reassuring me that it could be so much worse. We headed out out out into the ocean, then finally tacked and headed back back back to the unseen coastline.

One mile before the chart insisted we’d duck behind Brooks on the last leg of our journey, the sun suddenly made an appearance, the headland loomed above us, and the water began to sparkle. A half mile later, the winds dipped to 14, and the chop disappeared. Another mile and we were well into the shelter of Brooks, the winds died to 5, and the swell disappeared. Even shaking out reefs didn’t help, and the motor went on. We were so hot we started shedding clothing, stripping the covers off the bimini, and turning on the fans.

Another mile behind the peninsula and the blow holes started spouting in every direction. The girls, fully recovered from nap and mal de mer, swarmed over the deck shouting and pointing. Dr C throttled back as a large pod of orcas herded fish past us and towards the shore. At one point a trio headed straight for the boat, blowing not 10 yards from our starboard bow. The girls bounced on the tramp as the beasts passed under them before emerging for air again 20 yards off the port. Fins were visible in every direction, tails occasionally flapped the water, and one broached and jumped partially out of the water. Dr C idled forward after their passage only to be brought up short again, this time by a pair of humpbacks. These were much much larger and much slower. They seemed to enjoy looking at our boat, and spent a good five minutes showing their humps as they circled us before moving on to something more interesting.

I took the helm threading our way into the microscopic dip in the shoreline that constitutes the Columbia Cove anchorage as Dr C and the girls continued their Discovery Channel moment on the bow. There, tucked between rock and headland, were our buddy boats s/v Indigo and s/v Mercedes. Like the orcas, dinghies flowed out from our friends towards our boat, greetings and invitations extended, and guidance on where to anchor proffered. Forty to fifty miles later through sail, gale and whale, it was time to settle in for sea stories and ale. Welcome home!

Brooks is a thumb of land pushing into the Pacific like a hitch hiker grabbing the nearest earthly plate to drift northwards. Apparently, this nearly square jut of land is the only part of Vancouver not covered by glaciers during the last ice age. It stands several thousand feet tall and funnels the prevailing summer northeasterly in a vicious hook around Cape Cook and Solander Island where winds are routinely 30 to 40 and at least 10 to 15 higher than everywhere else.

As a result, we all timed the weather window carefully, hanging on hooks in or near Winter Harbor for a few days until satisfied with the reports off Solander and South Brooks. The sail boats were, of course, the first to leave the harbors. We swarmed out of Quatsino Sound, little pickup sticks bouncing vertically on the waves as we coalesced from north and west towards our course at the first waypoint off Kwakiutl Point. The wind freshened inexplicably from the east to 15 and the horizon sparkled with the handkerchief dots of main sails and jibs happily taking advantage of the beam reach for the first leg.

Just as all our sails went up, the power boaters steamed by thumping out cross wakes which were immediately lost in the developing chop created by an easterly wind and a northwesterly swell. Their objectives were no doubt considerably more ambitious than our own, bypassing the hidden coves of South Brooks entirely and heading deep into the friendly harbors and calm waters of Kyuquot Channel. There was also the practical consideration of the weather report. Winds nasty in the morning, dying off mid day, returning with a vengeance in late afternoon. Our p/v compatriots were simply getting while the getting was good.

We, however, were sailing into a fog bank as the winds shifted finally to their usual northwest and picked up to 20. The seas were only 2 meters. Only. The girls and I are complete noobs in the world of oceanic voyaging so six feet of steep wave with white caps was both intimidating and sickening. One by one, the girls went down with gimpy tummy. No one tossed anything smelly, but I settled them all down with blankies, stuffed animals, and motherly love, and they promptly followed the body’s most useful defense against seasickness -- they passed out. This left Dr C and I on the deck with no company. All the other boats, the shore, and the horizon were lost in a dense blanket of mist.

I said 35 miles, right? But that was, of course, assuming we followed the coast line. We never follow the coast line. We never follow a straight line. We are a sail boat, so of course the wind never permits us to travel the shortest distance. Instead, we headed off into the deep blue in a course somewhat orthogonal to our destination. The winds were cold and wet, the skies grey, the water slate and dusted with spray. Tracking via the chart plotter, backed up by our handheld GPS and chart, was the only indicator we were making progress. It all looked the same. Seas high and choppy, steep waves with short periods, wind steady 23 gusting occasionally to 30. Dr C kept reassuring me that it could be so much worse. We headed out out out into the ocean, then finally tacked and headed back back back to the unseen coastline.

One mile before the chart insisted we’d duck behind Brooks on the last leg of our journey, the sun suddenly made an appearance, the headland loomed above us, and the water began to sparkle. A half mile later, the winds dipped to 14, and the chop disappeared. Another mile and we were well into the shelter of Brooks, the winds died to 5, and the swell disappeared. Even shaking out reefs didn’t help, and the motor went on. We were so hot we started shedding clothing, stripping the covers off the bimini, and turning on the fans.

Another mile behind the peninsula and the blow holes started spouting in every direction. The girls, fully recovered from nap and mal de mer, swarmed over the deck shouting and pointing. Dr C throttled back as a large pod of orcas herded fish past us and towards the shore. At one point a trio headed straight for the boat, blowing not 10 yards from our starboard bow. The girls bounced on the tramp as the beasts passed under them before emerging for air again 20 yards off the port. Fins were visible in every direction, tails occasionally flapped the water, and one broached and jumped partially out of the water. Dr C idled forward after their passage only to be brought up short again, this time by a pair of humpbacks. These were much much larger and much slower. They seemed to enjoy looking at our boat, and spent a good five minutes showing their humps as they circled us before moving on to something more interesting.

I took the helm threading our way into the microscopic dip in the shoreline that constitutes the Columbia Cove anchorage as Dr C and the girls continued their Discovery Channel moment on the bow. There, tucked between rock and headland, were our buddy boats s/v Indigo and s/v Mercedes. Like the orcas, dinghies flowed out from our friends towards our boat, greetings and invitations extended, and guidance on where to anchor proffered. Forty to fifty miles later through sail, gale and whale, it was time to settle in for sea stories and ale. Welcome home!

Friday, February 15, 2008

Doing More With Less - Soap

The boat teaches many lessons in conservation. This is the second in a series of posts about how we boaters do more with considerably less. The tips are valid for land based life as well, though, so hopefully folks can use some of these ideas.

* * *

Have you ever seen a street drain with a little fish painted next to it? The fish tells you that anything you pour down that drain goes directly to a natural, nautical environment, be it creek, river, lake, or ocean. The objective of the fish relief is to make you feel guilty about pouring paint, machine oil, and dish soap down the drain.

I suspect as a public policy, the fish are a failure. It is difficult for the average American to comprehend the connection between his driveway and a river nearly a mile away.

Living on the boat, it is considerably more difficult to ignore the connection between drain and fish. For one thing, every morning you can watch the toothpaste spit emerge from a thru hull and dribble down the side of your boat to float in lily pads of minty fresh goodness. Scrubbing down the boat during an average boring passage produces a wake of cheerfully bobbing soap bubbles while dishwashing at anchor results in a bathtub ring of food particles and bacon grease adhering to your hull like the ghosts of dinners past.

So guilt alone drove the family to consider how we could clean things without killing fish. Ultimately, it comes down to that old saw, “The solution to pollution is dilution.”

Dilute Everything – There is not a single soap product distributed anywhere that is not packaged in solutions that are a minimum of ten times stronger than required to do the job. Now the environmentally friendly packages such as Seventh Generation and Simple Green explicitly tell you this. It turns out, though, that the 1:10 ratio works for everything from window cleaner to hair conditioner.

In fact, there are products you can dilute at an even higher ratio. Ivory dish soap, for example, can be diluted in a ratio of roughly 1:30. We put about a half ounce in the bottom of a small bottle and fill it up with fresh water, returning the “source” to the storage locker.

Use Less – Even diluted, you are still using too much. Whenever you can, don't put the soap in water. Don't put it in a bucket or a sink. Instead, apply the soap directly to either the item being scrubbed or a scrubbing device. That little bottle of diluted dish soap lasts us for nearly two weeks through the simple expedient of never putting the soap on either the dishes or in the sink water. We apply it the sponge and can generally make it through an entire meal's worth of dishes with two small applications.

Use Something Else – Very dilute vinegar is a great cleanser. Salt water is surprisingly cleanifying. Elbow grease and fresh water do wonders.

Warm the Water – I have no idea why, but soaps like warm water. You probably know that dish soap positively FOAMS when it hits hot water. However, the same is true of shampoo, laundry soap, and toothpaste. It's hard to get used to brushing with warm water, but you can get much cleaner teeth with much less paste if you do so. For shampoo, foam it up in your hands with hot water before slapping it on your head.

Make Your Own – For Winter Solstice this year, Dr C made soap for all the ladies in his life. From this exercise, we learned a few very valuable things:

Do Without – There are a lot of things we clean in the Real World which just stay dirty on the boat. It turns out that disinfecting everything is probably doing more harm than good in any case, creating nasty antibiotic- and disinfectant-resistant bacteria. There is no fear of that on our boat. I can't think of a single sanitary item on the entire vessel.

* * *

I think everyone should live for a week watching their every effluent, body fluid, and ounce of waste water float behind their home in sludgy, gray pools. It would take a very hard hearted or extraordinarily stupid person to fail get the hint. Soap is not good; it blows bubbles.

* * *

Have you ever seen a street drain with a little fish painted next to it? The fish tells you that anything you pour down that drain goes directly to a natural, nautical environment, be it creek, river, lake, or ocean. The objective of the fish relief is to make you feel guilty about pouring paint, machine oil, and dish soap down the drain.

I suspect as a public policy, the fish are a failure. It is difficult for the average American to comprehend the connection between his driveway and a river nearly a mile away.